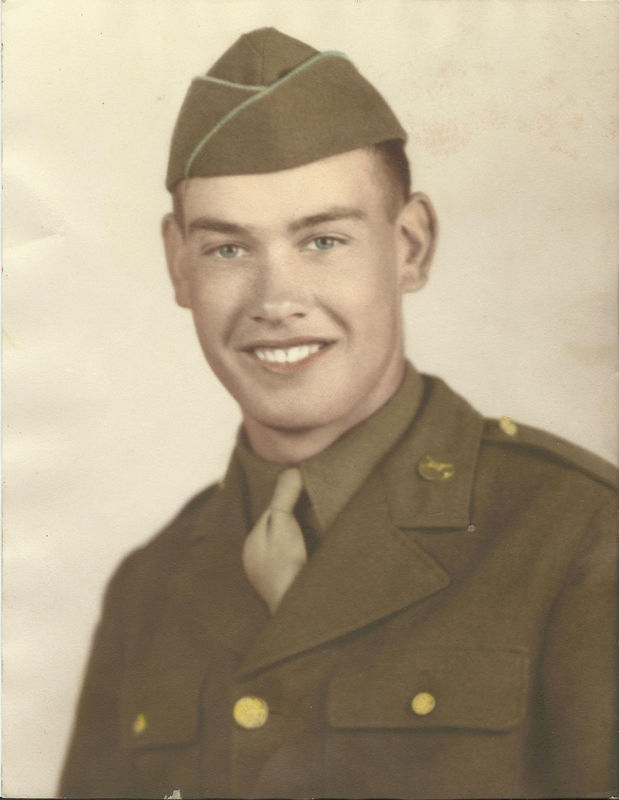

Glenn Biddy

One of the few surviving WWII vets: Glenn Biddy

Another veteran whose life was brought to California because of the Great Depression was Glenn Biddy. Born in La Junta, Colorado on November 26, 1925, Biddy and his family were forced to move to California following the onslaught of not only the Great Depression but the Dust Bowl as well. They eventually settled in Cutler, California, a community in Tulare County just 40 miles south-east of Fresno. From here, Biddy graduated from Orosi High School. Soon after, he was drafted. “I tried to get into the Air Force, but they said ‘no,’” he was known to joke with a smile. But if there was ever a moment where Biddy doubted his resolve and willingness to engage the looming Japanese threat, all those feelings of doubt quickly evaporated after hearing the news that his older brother, Graham, was killed during active duty in the Philippines. Devastated all the while, Biddy was eventually deployed to Okinawa to aid in the United States’ push into the Pacific Ocean. When he arrived on the island shores on April 1, 1945, the U.S. Navy had already surrounded the island, having engaged kamikaze fighters overhead. Over the course of 82 grueling days, Army troops along with the Marines eventually took over Okinawa, further stabilizing America’s control over the Pacific.

After the war’s end, Biddy joined the United States Army Reserves in the 11th Airborne Division. During the 1950’s, he returned home to Cutler, California, content in ending the life of a warrior for one where he could help his parents work their 40 acres of farmland. Later, he found a job as a field tech for the Burroughs Corporation, a major American manufacturer of business equipment, where he’d work for 38 years. Biddy moved to Stockton in 1977 and later to Lodi, California in 1982.

In 2014, Glenn Biddy was diagnosed with myeloma cancer and died in 2015. However, he left with his family and the entire Lodi community a legacy that would immortalize him. A key component of that legacy was the ethnic and cultural tolerance he expressed during his 33 years as a citizen of Lodi. One might recall that, during WWII, one of the fifteen Japanese detention centers managed by the Wartime Civil Control Administration was located in Stockton – the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds to be precise. The Delta region, like most of the regions spanning California, was home to an extreme fear of Japanese and Japanese-Americans living in the United States. This anxiety, characterized by suspicion and prejudice, was one Biddy never understood, one that he believed to be a baseless phenomenon. According to reporter James Striplin, “he never hated the Japanese, he said. After the war he learned to appreciate the people, who became more open to the American troops.” In fact, several of Biddy’s own Japanese-American classmates had been put in internment camps. “When he was in charge of organizing his high school reunion, those students said they weren’t able to join because they never graduation from high school." Biddy happily advocated on their behalf, allowing and arranging for their involvement in the reunion.

Had it not been for Biddy’s involvement with the American Legion, “the nation’s largest wartime veterans service organization,” his message of cultural tolerance would not have transcended into Lodi’s entire community of veterans. It was in 1920 when the American Legion (AL) established a chapter in Lodi called “Post 22,” the establishment of which occurred only a year after the AL became established nationwide. AL posts, such as Lodi Post 22, oftentimes serve as the central social hub for a town’s veteran community. Since almost every major national veterans organization in the U.S. has established a regional chapter within San Joaquin County (including groups like the Military Order of the Purple Heart, AMVETS, and Vietnam Veterans of America); veterans have become among the most powerful and influential members, able to shape a community’s social attitudes regarding any given topic. In Biddy’s case, he used his role as a ranking member of his American Legion post to help San Joaquin County move past its history of harsh treatment towards the Japanese community – starting with white Delta landowners’ unjust exploitation of Japanese laborers amid the turn of the 20th century, and including California’s role in exacerbating the country’s jaded perception of Japanese and Japanese-Americans after the Pearl Harbor attack, bringing the nation closer to the signing of Executive Order 9066.

source: James Striplin, “Lodi World War II veteran Glenn Biddy shares stories of Okinawa and occupation of Japan,” Lodi News (November 20, 2014).