Businesses

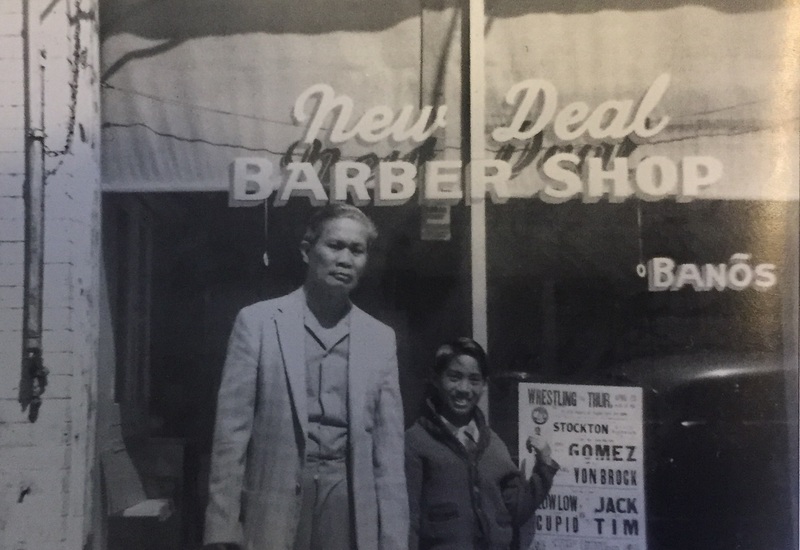

The Filipino community thrived in the central valley of California and became a dominant area for migrant farmers to settle. The central valley provided year-round work for farmers which resulted in Filipino communities seeking recreational entertainment and other services in the local area and from 1924 to 1975, the Stockton city directory records listed over sixty businesses owned by Filipinos. In Dawn Mabalon's chapter of Positively No Filipinos Allowed: Building Communities and Discourse she includes the histories of the famous Lafayette Lunch Counter purchased in 1931 by her grandfather and Carmen Saldevar whose husband, Fernando Saldevar, owned one of the four barbershops as well as the Stockton Pool Hall (pictured above). Many businesses owned by Filipinos included hotels, barber shops, restaurants, grocery stores, community groups, and even a few newspaper publications with most businesses located within the four-block Little Manila district.

The businesses on El Dorado Street were the heart of Little Manila, the street where people spent most of their leisure time either in card rooms or dance halls, grabbing lunch from the lunch counter and retiring to home in South Stockton, or in relatively inexpensive rooms in Filipino-owned hotels. Most notably, Billones Photography, Juanitas Grocery, Aklan Hotel, Quezon Hotel, Candelario’s Restaurant, P. D. Lazaro Tailoring, Hollywood Bath House Shoe Shine Stand and Barber Shop, Philippine Barber Shop, Three Star Pool Hall, Rizal Social Club (a dance hall), Lighthouse Mission (a Protestant mission). After the war, the community and businesses in Little Manila thrived and provided a permanent home for Filipinos in their small district of downtown Stockton.

In the chapter “Race, Class, Suburbanization, and Inner City ‘Blight’” of Positively No Filipinos Allowed, Dawn Mabalon describes the different post-World War II factors that contributed to the expedited redevelopment of urban inner cities across America and how those nationwide efforts affected the businesses in Little Manila. The major pattern she cites included: “white flight to the suburban divisions, the emergence of suburban shopping malls, and massive freeway construction”. Beginning with housing, Dawn suggests that the FHA lending practices in place at the time barred non-whites residents from being able to own homes in the new northern housing developments. This left Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, Mexican, and Black communities with housing choices in downtown, south, or east Stockton.

As the more preferred northern and western parts of Stockton became inhabited by white communities, much of the federal funding went along with it leaving downtown communities such as Little Manila to suffer and deteriorate. At the same time, legislation authorized over one billion dollars in grants and loans to buy “blighted” lands. Land deemed by experts as areas that proved to be in economic decline for one reason or another were considered to be suffering from either “physical blight” or “urban blight” and were put up for auction . Efforts like these occurred nationwide and spurred the redevelopment of low-income neighborhoods and businesses. In Stockton, these efforts began in 1952 as the Stockton City Planning Commission advocated for the use of federal funds for redevelopment, specifically of the central business district (including Little Manila) and the West End resulting in the creation of the Urban Blight Committee.